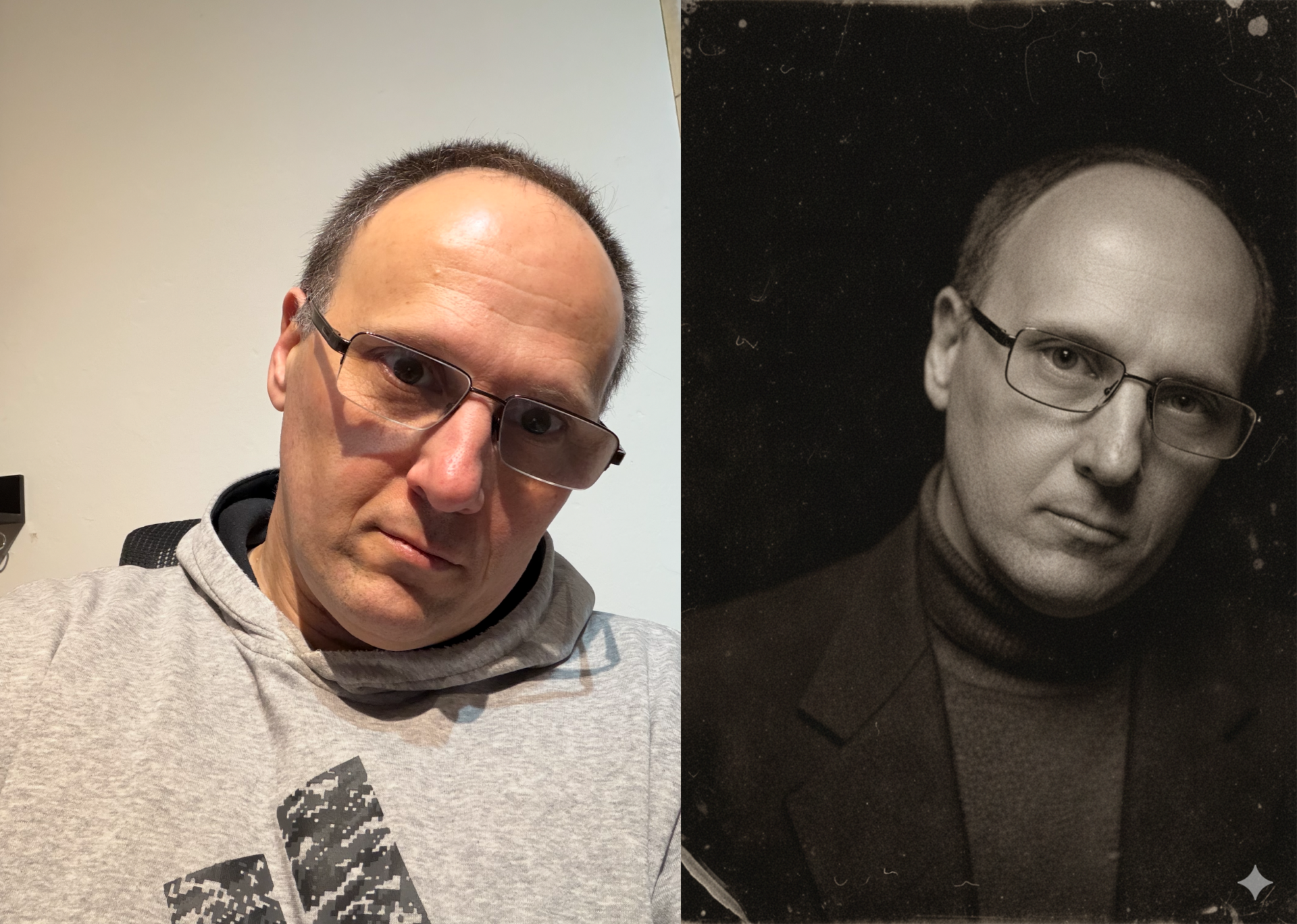

I started with a very normal, very unromantic thing: a quick selfie. Bad light, modern hoodie, “just get it done” energy. The kind of photo you take when you don’t want to think about photos.

And then I looked at Steffen Diemer’s work again—and felt the opposite of “quick.”

Diemer’s works don’t look like images. They look like objects. Like you could pick them up, tilt them under a lamp, and watch the surface behave. They carry that strange combination of sharp presence and fragile decay that only physical processes create.

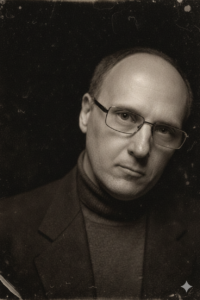

So I set myself a challenge: could I push AI far enough that the result stops feeling like a digital filter and starts feeling like a physical artifact?

Not “old-timey.” Not “vintage preset.” I mean an image that convinces you, on first glance, that it has weight, chemistry, and time inside it.

That’s how this project began.

Why Diemer is so hard to imitate, and so worth studying

Steffen Diemer doesn’t just shoot a photo. He builds a slow, chemical chain of decisions that ends as a single, unique plate. On his own site he describes working with the wet collodion process and creating unique pieces on black glass.

The wet collodion process itself is obsessive: a cleaned glass plate is poured with collodion, sensitized in silver nitrate, exposed while still wet, then developed, fixed, washed, dried, and varnished. And timing matters because the plate loses sensitivity as it dries.

That “pressure of time” becomes part of the look. The image isn’t only captured—it’s won.

What hit me most is that Diemer’s practice isn’t nostalgia. It’s discipline. One text about his work notes he spent three years and a six-figure investment to master the technique, which only few people worldwide truly command.

So yes, I knew this would be arrogant to even attempt.

Which is exactly why I wanted to attempt it.

My question wasn’t “Can AI make it prettier?”

My question was: Can AI be forced to respect material reality?

Because most generative imagery is fast and frictionless. Wet-plate is neither. Wet-plate is constraint, slowness, and imperfection—with rules that don’t care about your deadlines.

That became the conceptual core of my experiment: teach a fast machine to imitate a slow craft without turning it into a caricature.

The workflow I ended up building

I used two roles of AI in parallel:

Gemini became my ruthless critic and creative director—the voice that kept asking, “Does this read as a physical plate, or as a digital costume?”

Nano Banana Pro became the tool in the “darkroom”, the place where I did precision edits and iterative refinements.

The key wasn’t one perfect prompt. The key was looping: generate, zoom in, fail, diagnose, re-edit, repeat.

At some point, I realized I wasn’t “prompting.” I was art-directing, with constraints so strict they sounded almost paranoid.

And they had to be.

The problems we had to solve (the ones that actually matter)

Early versions looked impressive at thumbnail size…and collapsed the moment you looked closer. That’s always the tell. Digital images tend to break under scrutiny, while physical processes tend to reward scrutiny.

The three most stubborn “digital tells” in my portrait were these:

The eyes were too perfect

In real wet-plate portraits, the exposure time makes micro-motion unavoidable. People don’t keep their eyes perfectly still for several seconds. My first AI versions gave me eyes that were too crisp—modern-sensor clarity wearing an antique jacket.

So I softened only the eyes—not the glasses, not the face, not the frame—to simulate that slight watery instability you get from a long exposure.

The face was clean, but the edges were dirty

This one is subtle and deadly. A lot of AI “wet-plate looks” do distressed borders like stickers—heavy damage at the edges while the center stays sterile.

A real plate tends to carry texture more consistently. So I worked on unifying the whole image with a faint glass-grain micro-texture that sits everywhere—enough to remove the “modern cleanliness,” but not enough to turn skin into noise.

The lens reflections didn’t behave like optics

Reflections are where AI often betrays itself because physics is strict. A controlled light source should read like a controlled light source. My reflections looked “busy” and chaotic—more like an algorithm trying to impress than a plate responding to a north-window highlight.

So I simplified the reflection to a single soft rectangular highlight with correct curvature—still believable, still optical, but calm.

This was the pattern of the entire project: not “add more,” but “remove the digital instincts.”

The moment it finally turned into an object

There was a point where the image stopped feeling “generated” and started feeling handled—like it had been through a process, like it had survived something.

The background shifted into what I can only describe as that wet-plate void: not a black wall, but black glass. The highlights on the forehead and cheek stopped looking like “lighting” and started looking like silver on a surface.

And suddenly the portrait wasn’t trying to cosplay history.

It was speaking a similar language of materiality.

Why this matters beyond one portrait

I don’t think the future of digital art is just higher resolution or better realism.

I think the future is material intelligence.

The next creative edge is not “Can AI draw?” It already can. The edge is: can we teach AI to respect the logic of real processes—chemistry, optics, time, gravity, friction—so that digital work gains the emotional authority of physical work?

For artists, this is not a threat. It’s a new studio.

But it demands a shift in mindset: you don’t get authenticity by asking for it. You get it by enforcing constraints until the image has no choice but to behave.

What this project changed for me as an artist

I came into this wanting a “Diemer-like portrait of me.”

I came out with something more valuable: a new way of thinking about authorship.

I wasn’t copying Diemer. I was studying his discipline—and building a digital process that forces similar rigor. The craft became the concept.

And personally, it reminded me why I make work at all: to find the line where control ends, where unpredictability begins—and where something alive happens.

AI can go fast. That’s its superpower.

This project was my attempt to make it slow.

And in that slowness, I found the part that felt like art.